In a world marked by a persistent digital divide, community-centred connectivity initiatives (CCCIs) are building bottom-up strategies to bridge that gap in ways that are grounded in people’s real needs. Access is not only about connecting to the internet. Bridging the digital divide involves access to infrastructure, to skills that ensure meaningful use, to enabling policies and legal frameworks and, critically, to financing mechanisms that allow these initiatives to be born, grow and become sustainable.

Securing funding for the development and maintenance of such projects remains a significant challenge. While pathways like grants, loans or investments exist, most are inaccessible to grassroots initiatives that provide connectivity from within the communities themselves. “How much money is needed to close the digital divide from an infrastructure point of view?” asked Carlos Rey-Moreno at a recent session on innovative regulatory strategies to digital inclusion at this year's Internet Governance Forum (IGF). “I believe there are too many conversations about costing and not as much about how investment could be used differently to enable other models,” he stressed.

Ultimately, what’s at stake is not just financial resources, but the challenge of providing meaningful connectivity services to those who are still unconnected due to the fact that they are left behind by traditional large telecom operators – generally because they are not interested in investing in those areas, since they are not profitable.

“We need to establish innovative financing and investment models that allow small and localised operators to thrive. In the financial sector, a lot of the interest has been focused on supporting the interests of capital and not supporting the interests of people,” reflected Rey-Moreno at the IGF session. “People in underserved communities are willing to take the risks expected from the private sector operators. They only need the tools for doing so,” he added.

“We need to establish innovative financing and investment models that allow small and localised operators to thrive. In the financial sector, a lot of the interest has been focused on supporting the interests of capital and not supporting the interests of people,” reflected Rey-Moreno at the IGF session.

Growing concern around the connectivity agenda

As early as when the initial World Summit on the Information Society (WSIS) meetings took place in 2003 in Tunis and in 2005 in Geneva, there was clear recognition that financing mechanisms were essential for building “a people-centred, inclusive and development-oriented” information society. Two decades later, it is increasingly evident that digital inclusion cannot be left solely in the hands of traditional telecommunications actors. New forms of socially driven investment and flexible financial tools are needed to support small, local and community-based operators.

The question on sustainability has long preoccupied those working to close the digital divide, especially in rural, remote and marginalised urban areas. While technical solutions and regulatory debates have often taken centre stage, the issue of how community connectivity initiatives are financed is now emerging and moving to the forefront. This shift highlights the growing awareness of the transformative role of CCCIs in digital inclusion, amid a sense of urgency driven by the crisis of global aid and the uncertainties of the actual funding landscape.

A chapter from the recent edition of Global Information Society Watch (GISWatch) highlights two financing strategies proposed in the WSIS process to provide financial resources to those unreached by commercial operators: the newly created Digital Solidarity Fund (DSF) and existing national universal service funds (USFs). The DSF was dissolved in 2009 due to a lack of funding. Meanwhile, as noted by the UN Inter-Agency Task Force on Financing for Development in 2022, USFs often fail to deliver in most of the countries that implement them, mainly due to excessive requirements that non-profit initiatives cannot fulfil. A policy brief from APC to the WSIS+20 review includes a pillar devoted to establishing innovative financing and investment models, highlighting: “With very few exceptions, and despite recommendations from the UN Broadband Commission and the ITU [International Telecommunication Union], among others, USFs are not designed to enable CCIs through funding. This needs to change.”

Bottom-up initiatives like CCCIs require policies and financial frameworks tailored to their realities and possibilities. Many community-led initiatives are forced to navigate complex funding systems, often facing requirements and expectations misaligned with their operational contexts and collective values. In this regard, the GISWatch chapter also calls for “additional sources of finance from non-traditional funders using innovative and flexible financial mechanisms, along with a regulatory environment that enables many more socially driven, complementary network operators to emerge, focused on bridging the digital divide rather than solely on profitability."

Along these same lines, the 2021 report Financing Mechanisms for Locally Owned Internet Infrastructure, developed by the Internet Society, Connectivity Capital, Connect Humanity and the Association for Progressive Communications (APC), identifies three primary financing strategies – grants/subsidies, equity and debt – and explores how these are being adapted to fit the unique structures and missions of local providers. It also puts forward practical recommendations for funders, governments and communities seeking to build sustainable models.

More recently, in 2024, a new milestone in this conversation was the side event that the United Nations Commission on Science and Technology for Development proposed on “Exploring innovative financing mechanisms for community-centred connectivity: A WSIS+20 agenda to leave no one behind”. This was a key multistakeholder space to focus on the need to look for new ways of financing community-centred connectivity initiatives, along with other key events this year: the 4th International Conference on Financing for Development, the IGF and the WSIS+20 High-Level Event.

A call to action emerging from research and dialogues

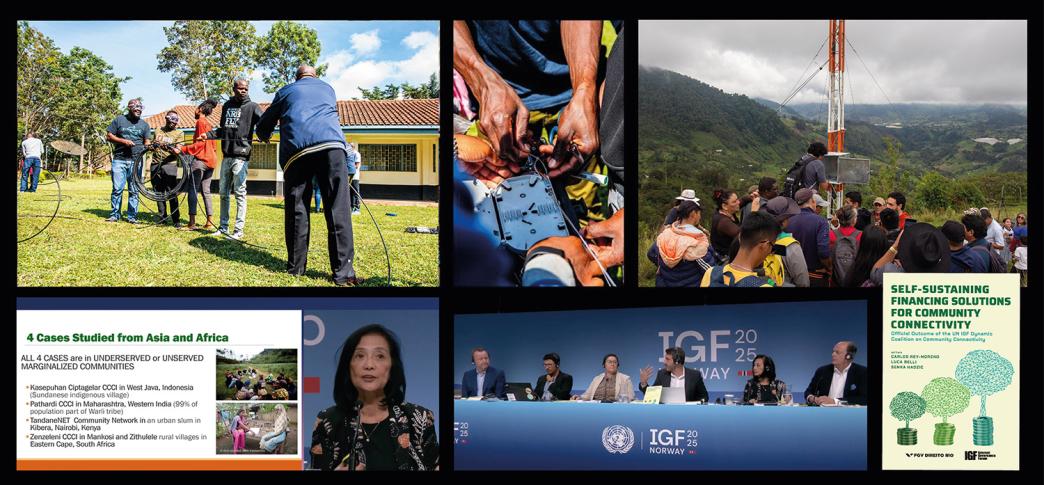

The question of how to finance community connectivity gained prominence at this year's IGF, especially during the launch of the book Self-Sustaining Financing Solutions for Community Connectivity and the panel session “Financing Self-Sustaining Community Connectivity Solutions”, where the authors of the chapters that comprise the book joined with partners and committed funders of CCCIs to share findings and reflections, pushing forward a vital conversation.

The book is the official 2025 outcome of the UN’s Dynamic Coalition on Community Connectivity (DC3). Moderated by Luca Belli, chair of the DC3 and editor of the book together with Senka Hadzic and Carlos Rey-Moreno, the panel shared highlights from each of the participants. “The report is not a collection of opinions,” said Belli. “It is a collection of facts, of very thoroughly researched papers that are backed with evidence and analyses of what could be the possible models spanning from blended finance to other solutions to support community network initiatives until what could be the social return on investment of these initiatives.” One chapter of the DC3 book is devoted to the Typology of community-centred connectivity initiatives, developed by the Local Networks initiative, mapping the complexities of different models that communities could implement.

The panel featured the presentation of the researches included in the edition, and also the perspective of partners, funders and donors largely working for connecting the unconnected and supporting community-centred connectivity initiatives. Chris Locke, managing director of the Internet Society Foundation, pointed to a key takeaway: the need to support “grantepreneurs” – actors moving from grant-based survival to financially autonomous operation. “We must ensure the right financing is in place to bridge the post-grant phase,” he commented, “while also helping organisations build the capacity to sustain themselves.”

Liza Dacanay of the Institute of Social Entrepreneurship in Asia (ISEA) introduced their study “Towards measuring the social impact and cost effectiveness of community-centred connectivity initiatives”. Through the usage of two key indicators, the social return on investment (SROI) and development indexing, the research assessed the social impact of four community networks in Asia and Africa. ISEA’s report found that CCCIs deliver more than internet access: they provide social inclusion services (like digital literacy) and transformational services (like local ownership of digital infrastructure). Over time, the study shows, CCCIs generate increasing social value, proving not just their cost-effectiveness but a transformative role in communities, particularly for women and marginalised groups.

Claude Dorion, a financial strategist for collective entities, co-authored the DC3 book's chapter on “Breaking the Financial Divide of Digital Divide”, and shared during the panel the results of another study that surveyed 85 community connectivity initiatives. His findings also show that while many initiatives generate strong social impact, from improving access to health services to building community cohesion, most struggle with capital expenditure, regulatory constraints and investor documentation demands. Dorion stressed the importance of blended finance models that combine, in a relational way, grants with other forms of capital to reflect the diversity of CCCIs’ financial realities.

This argument was echoed by Brian Vo and Nathalia Foditsch of Connect Humanity, who shared their investment due diligence across nine CCCIs in Africa, Latin America and Asia. They called for the creation of a finance ecosystem tailored to community networks – one that treats them as infrastructure investments, not charity cases. “We need better capital, technical assistance funding, and a mindset shift,” Vo emphasised.

Other partners on the panel also echoed this perspective. Carl Elmstam, policy specialist on digital for development at the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida), and Alessandra Lustrati, head of Digital Development at the UK Government’s Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO), both acknowledged the need to rethink how community networks are evaluated, financed and supported. Elmstam highlighted the fact that focusing on these tools for communities “is basically talking a different language. Right there, there is clearly a need for facilitation or even interpretation to accompany the initiatives,” he proposed as an action to be developed for making the finance world more approachable for communities. He also advocated for layered financing approaches, where donors like Sida or the European Commission can offer guarantees and risk-sharing tools to unlock private and development finance.

Lustrati, meanwhile, reflected on the conversation that was being held. “Everything that we're discussing in this room today might sound a little bit theoretical. But it is actually something extremely concrete that has a direct impact on people's lives.” She also emphasised the importance of linking high-level policy reform with local experimentation, enabling social enterprises and community networks to test sustainable models at scale.

Learning from communities

Through an open microphone segment, the panel included voices from communities. James Nguo of the Arid Lands Information Network (ALIN) in Kenya and Gustaff Harriman Iskandar of Common Room Networks Foundation in Indonesia, both APC member organisations, reminded the room that connectivity is a lifeline, and that CCCIs are driven not by profit, but by social good. Nguo stressed the need for funding models that recognise the low-income realities of many communities, where paying even USD 10 per month for internet access is unaffordable. “When you look at the equipment required to expand the network in order to serve a large area, you realise that you need a lot of money to be spent on it.” Nguo noted that most of these community networks are relying much more on volunteers. “I think it's high time that governments and donors looked at them as social good and continued to pump money just like they do in health and education in order to have many people enjoying the benefits of digital opportunities,” he added.

Iskandar pointed out another concerning issue for the sustainability of CCCIs: most sites often rely on alternative energy systems and operate in places without any electricity grid at all. Pointing to the example of a community network run by Common Room in Indonesia, he explained, “We have to use a micro hydropower supply and the community has been running this plant for quite some time. They are very skilful for that. So there are strong connections between green energy supply and community-centred connectivity.” This example highlights the resilience that comes from local ownership, he emphasised.

In this new stage of the conversation on financing mechanisms for CCCIs, “solution” is a recurrent word in the analysis. As proposed in the conclusion of the DC3 book, authored by APC’s Mike Jensen, Anriette Esterhuysen and Josephine Miliza, instead of seeking a one-size-fits-all solution, the way forward could be to move towards a diversified ecosystem of innovative financing and investment models. In their words:

“Despite the high capital requirements and operational challenges these initiatives face, their ability to provide meaningful connectivity and bridge the digital divide in a more cost-effective way, and foster local ownership, sets them apart as powerful drivers of equitable digital transformation.”