In the 10th episode of the podcast series Routing for Communities, an initiative from the Association for Progressive Communications (APC) and Rhizomatica, Edinson Camayo presents his reality to us as one of 1.9 million Indigenous people in Colombia. He is part of the Nasa ethnicity, living in and representing the Pueblo Nuevo reservation, or the Khwe'nxa Cxhah people. By listening to him we learn that in the Nasa language, Khwe'nxa Cxhah means “children of the water, grandchildren of thunder”. The meaning of the word that names the people shows that the way the Nasa perceive their existence on the planet is through a lineage that derives from natural elements of the Earth. This connection is vital as well central to the world view of this population. More than an anecdotal fact, this brings context to the continuous fight for land, culture and Indigenous autonomy in Colombia.

The Nasa people are fighting for the right to remain autonomous, despite strong opposition and continuous violent colonial oppression that takes many forms, including the lack of access to rights such as the right to autonomous communication infrastructure. However, for the Nasa people, there is strength and resistance in the idea of carrying in their core identity the characteristic of being children and grandchildren of something bigger than their own humanity. The water and the thunder are the elders, to be respected, to learn from and listen to. They are knowledgeable and help guide the collective path. There is something singular and outstanding about the perspective of the Nasa people that, in contrast, makes me think of the quote from US writer Mark Twain that is still enthusiastically embraced by the real estate business today: “Buy land, they're not making it anymore.” One perceives Earth as a mother that should be protected from harm, while on the opposite side of the spectrum is an aggressive possessiveness that views the Earth as resources and commodities, fencing, artificially dividing and exploiting it to exhaustion.

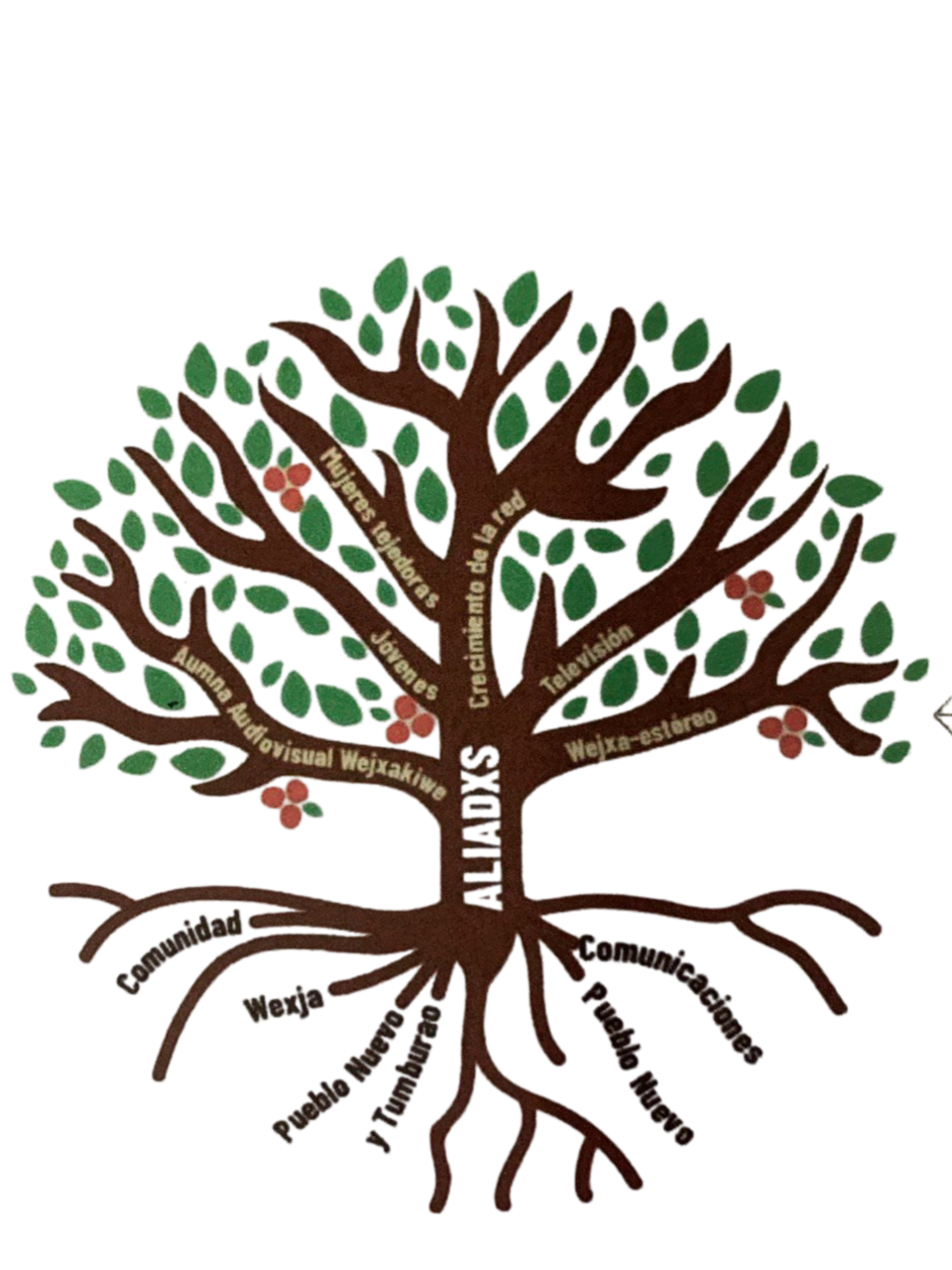

In November of 2024, the Local Networks initiative (LocNet) and Colnodo partnered to bring together community networks from all over Colombia for the Third National Encounter of Community Networks in Bogotá. I had the opportunity to attend the gathering, where I had the pleasure of meeting one of the members of the Nasa community featured in the podcast episode. Juan Pablo Camayo, Edison's cousin, shared with me more about their fight for Indigenous technological autonomy and how the Nasa people in Cauca involved in the community network there think of their community structure: it is shaped like a tree, with several groups of people and initiatives undertaken by them that converge into a trunk of alliance.

The community radio and TV station, the local youth, communicators, the different villages of the territory and the connectivity efforts all are parts of this alliance. I learned that the Nasa have a long tradition of community work, participation in community councils for decision making and group discussions around the preoccupation with strengthening their own cultural identity. Through such processes they resist and face the ongoing threat of erasure of their language, a strong aspect of colonial violence in the country. In 13 years, the number of speakers of their native Nasa language decreased by 30%, a statistic that mirrors the disappearance of Indigenous linguistic heritage around the world. From this need to expand the protection of land and culture, in partnership with Colnodo, the Jxa’h Wejxia Casil Community Network was created in 2020. The “Network of the Wind” again turns our attention to the organic operation of natural earthly elements from which to draw inspiration and learn. It is a demand for the right to access a portion of the sky in order to transmit knowledge, defend the land and communicate freely.

One of the branches of this tree of alliances is composed by the Mujeres Tejedoras, or women weavers. These women are highly valued in the territory for their gift of knowledge keeping. They vary in age within the group, making sure the tradition of the weavers is passed along from generation to generation. The weavers’ work goes beyond handicraft, as the artifacts they make with their hands contain one of the most important pillars that sustain their tradition and way of life: the story and knowledge of the community. This knowledge is imprinted in the work, and through the work they guarantee that it is not forgotten. The chumbes are belts that tell a story. Even a belt’s seemingly simple design, made up of rectangles, contains profound knowledge, symbolising past, present, future and the point of balance between the three. They keep the collective knowledge of traditional ways of planting, harvesting and building, as well as reinforcing the cosmovision of the community. They are worn wrapped around the waist, in a circular manner that “reminds us that time is not linear but comes back around, as a spiral,” Juan tells me.

Weaving relationships in the community

The connection between the weavers and the community network is strong, as they mutually support each other just like branches and roots of the same tree. The weavers create patterns to capture and teach the wisdom of the collective and that is seen as a gift they offer. In return, the local community network is supporting the weavers by facilitating the outreach of their work through connectivity. This year the weavers will begin exporting their products to Spain, a possibility that arose after the network enabled communication between the women and third parties that were able to find them and their products through the internet. The Um Nees group is present online and their work can be seen here.

This connectivity helps set a path for financial sustainability, a key aspect of the emancipation of women across the globe. In fact, one of the feminist pursuits of various community networks is using connectivity as a means to divulge the work of women with the community, as well as investing in women's economic empowerment through capacity building. The network is built to support life, and Juan Pablo is proud to say that there have been seven births that have happened successfully because of the possibility to call for medical assistance at the time of the deliveries. These children and mothers are “alive and part of the community because of the possibility of connectivity,” he tells me.

Through the network, the Nasa people’s stories, knowledge, advice, warnings, expressions of love and anything else they wish to communicate travels through the wind. Information searching for paths across the sky to get from sender to recipient.

The myth of the scarcity of the spectrum

Meanwhile, a different NASA, the one run by the US federal government, approaches spectrum from the regulator’s perspective and states: “Use of the radio spectrum is regulated, access is controlled and rules for its use enforced because of the potential for interference between uncoordinated uses. Spectrum is scarce because at any given time and place, one use of a of a frequency precludes its use for another purpose.” In a piece for GenderIT.org, Bruna Zanolli, my colleague in the LocNet initiative who specialises in community-centred telecommunications and digital care, drawing on the principles of intersectional feminism, social and climate justice and popular education, opposes this idea and approach, proposing a view of radio spectrum as a feminist common good. She invites us to "look at some characteristics of the radioelectric spectrum: it can be used at the local or global level; since spectrum is about energy flow, it never runs out. It’s not finite and scarce, contrary to what the commercial-use strategy on spectrum would have us believe. It’s a common good. [...] With digital radio technology it’s possible to have four times the number of broadcasts in the same band, because digital signal occupies less space than analogue signal.”

The electromagnetic spectrum is composed of frequencies of radiation that propagate energy and travel through space in the form of waves. Longer wavelengths with lower frequencies make up the radio spectrum, widely used in telecommunication. To prevent interference between different users, the generation and transmission of radio waves is strictly regulated by national laws, coordinated by an international body, the International Telecommunication Union (ITU). However, there are possibilities of sharing and coordinating use of bandwidth if there is political will to endorse community-centred communication and connectivity.

The Jxa’h Wejxia Casil network relies on this use of a bandwidth of spectrum to connect their territory, as do so many community networks in Colombia who fight for the right to use the wavelengths to advance their autonomy. To move away from the crystallised idea of spectrum as a scarce resource, protected from organised communal use by citizens and with access only given to large information and communications technology (ICT) companies, is central to Adriana Labardini, also my colleague in LocNet. Adriana is a lawyer specialised in ICT, who asks for urgent revisions of how public policy regulations are built. She suggests that we “approach them in a holistic manner, not susceptible to oscillations depending on the political ideologies of each government" and reminds us that "digital transformation programmes are cultural transformation programmes. Transformation of processes, of the ways of producing, distributing and consuming goods and services.” In an interview for the Routing for Communities podcast, she makes clear that "the myth that the spectrum is always scarce is just that, a myth. In rural and remote areas there are huge amounts of spectrum that no one uses and that could be benefiting local schools, clinics, individuals, small businesses, farmers and artisans, to give them an opportunity of sustainable development on their own terms."

Recently, the Colombian civil society organisation Colnodo started a campaign advocating for a regulatory framework that enables the use of spectrum by rural communities, ensuring continuity of connectivity and mobile internet access in remote, unconnected rural areas. We support the #EspectroParaComunidades (Spectrum for Communities) campaign of the community networks movement in Colombia, another way in which communities strive for space, water, air and land to keep their traditions alive. You can connect to the tree of the Nasa people of Cauca by accessing their web radio station and their audiovisual initiative. You can also learn more about the Jxa'h Wejxia Casil Community Network or watch a recently launched documentary on the community networks initiatives in Colombia.

Luisa Bagope is a documentary director and project coordinator interested in community technology. For 10 years she has been registering cultural and political manifestations that aim to reshape the way we approach the environment and collectivity. She is currently the regional gender coordinator for Latin America and the Caribbean for the Local Networks initiative.

Photos: Courtesy of the author