Across rural Kenya and townships in South Africa, a digital shift is quietly underway. It’s not coming from tech giants or fibre monopolies; it's being led by local community networks, people-powered efforts to connect the unconnected and equip communities with the tools to shape their digital futures. From Kilifi to Meru, from Mathare Valley to Mankosi, these community networks aren’t just installing Wi-Fi; they’re building skills, confidence and inclusive ecosystems. Supported by the Association for Progressive Communications (APC) and Rhizomatica through the Local Networks (LocNet) initiative, these projects offer powerful lessons about what it really takes to bridge the digital divide beyond infrastructure.

Here are five key learnings from recent community network initiatives in Kenya and South Africa.

1. Skills before signals: Capacity building is the cornerstone

If one theme emerges across all community network projects, it’s this: connectivity alone isn’t enough. Communities need skills to deploy, maintain and adapt networks over time. At the Athi Community Network in Kenya, a micro-grant from LocNet enabled the recruitment of a full-time trainer who lived with the community and taught everything from pole fabrication to fibre optic splicing.

Connectivity alone isn’t enough. Communities need skills. Photo by Dunia Moja.

Within months, villagers who had never touched a router were confidently installing Starlink kits, managing Cambium radios, and wiring fibre links between schools and health centres. Likewise, in South Africa, networks like Zenzeleni and Black Equations invested in professional certifications like Certified Fiber Optic Technician (CFOT) and Mikrotik, giving young technicians not just skills, but recognised credentials that can open future doors.

What can we learn from them? True sustainability comes not from donor-funded installs, but from investing in local human capital.

2. Gender inclusion requires intentional design

Most community networks are challenging deeply rooted gender gaps in tech, but success isn’t accidental. It comes from deliberate programme design. V-NET in South Africa didn’t just include women in deployment; they upskilled female technicians to configure routers and manage private clients, moving beyond installation tasks traditionally assigned to women.

The Siaya Community Library in Kenya trained over 5,800 students in digital literacy using gender-responsive methods, improving confidence and participation especially among girls.

Gender inclusion must be embedded in training and leadership. Photo by Dunia Moja.

Dunia Moja, also in Kenya, created safe, inclusive storytelling spaces where young women could learn media skills, influence narratives, and join digital policy dialogues.

What can we learn from them? Gender inclusion isn’t a checkbox, it's a design principle that must be embedded in training, mentorship, content creation and leadership.

3. Peer learning beats top-down training

Community networks thrive when they learn from each other. Across both countries, the power of peer exchanges emerged as a core catalyst for growth.

The Amadiba Community Network’s exchange with Zenzeleni in South Africa helped them install new hotspots and spark conversations with women about digital leadership.

Mamaila Community Network’s monthly learning sessions (South Africa) turned into a regional knowledge hub, connecting community networks across the continent. In Kilifi (Kenya), Dunia Moja’s vocational students reverse-engineered digital tools and then taught each other launching mobile hotspots like the “Boda-Fy” motorcycle – a moving Wi-Fi station.

What can we learn from them? When peers teach peers, learning is faster, more inclusive and culturally grounded.

4. Infrastructure must be flexible and community-led

Terrain challenges, internet service provider (ISP) constraints and weather disruptions all forced community networks to adapt their architectures, and their ingenuity was inspiring. The Athi Community Network started with a centralised design, pivoted to fibre, then reconfigured back to a distributed Starlink-powered model to overcome terrain and backhaul issues.

The trainee cohort at the site during the installation of a guyed wire tower. Photo by Athi Community Network.

Black Equations in South Africa developed a “fibre-to-flat” model for dense urban housing in Ocean View. Kijiji Yeetu’s Dala Scratch 3.0 used coding bootcamps to spark digital interest where infrastructure was still developing, showing that content and skills can lead infrastructure, not just follow it.

What can we learn from them? Community networks work best when their models are shaped with, not for, the communities they serve and when they’re designed to evolve.

5. Digital inclusion isn’t just access, it’s opportunity

Perhaps most powerful are the stories of individual transformation.

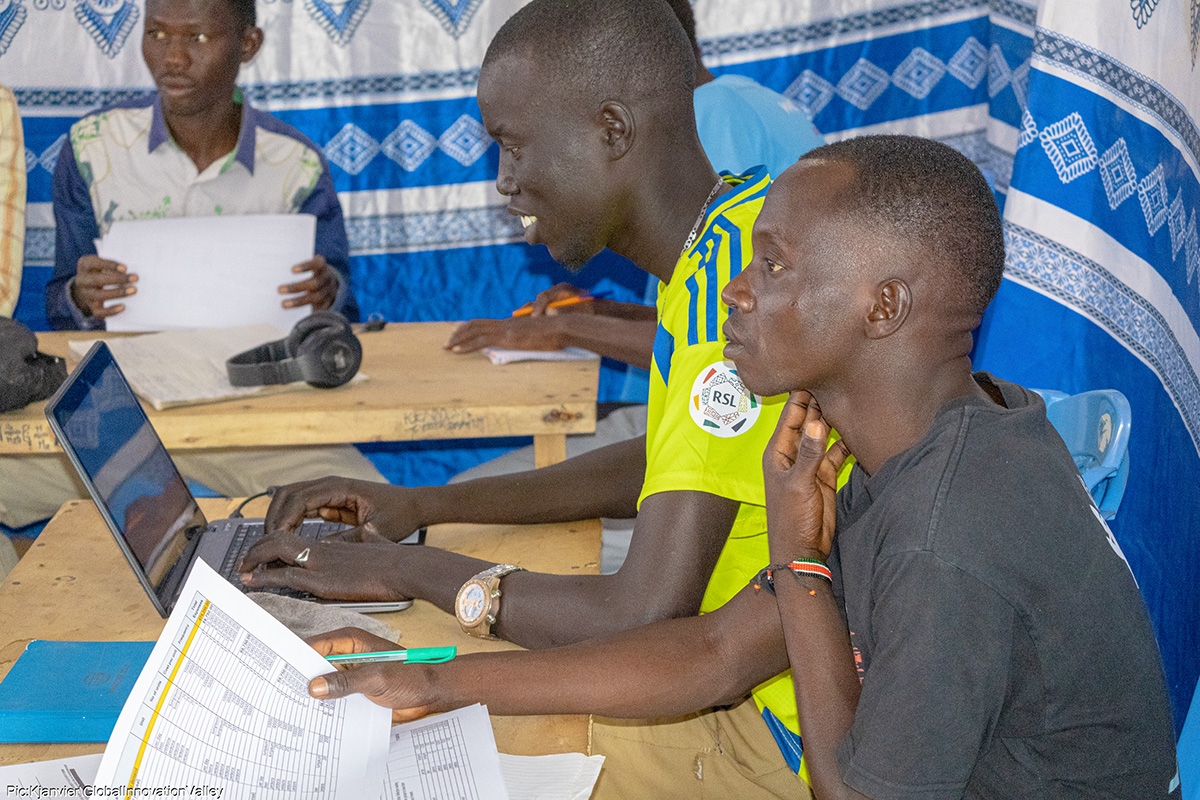

Youth refugees move to accounts lead after financial literacy training. Photo by Global Innovation Valley.

A high school student in Ocean View who used V-NET through grade 11 and is now studying for a BSc in Audiology with five distinctions. Buom, a refugee youth in Kakuma, who moved from volunteer to accounts lead after financial literacy training with Global Innovation Valley. Children in Kijiji Yeetu’s coding bootcamp, many using computers for the first time, creating Scratch-based games and animated stories that mirrored their communities (learn more about these and other grounded stories).

What can we learn from them? The real power of connectivity is what people do once they’re online. And when communities own the tools, magic happens.

The future is community-built

These stories and learnings make one thing clear: Africa’s digital future is being built from the bottom up. With the right training, trust, and technology, community networks are not just closing the access gap, they're redesigning the digital economy to work for everyone. The main challenge community networks face is to promote meaningful connectivity for those still unconnected, through access to infrastructure, connectivity and capacity building, enabling regulations and policies, and funding that allows them to grow and be sustainable. If you're a policy maker, donor or technologist reading this, the call is simple: invest in communities, not just in megabytes. Fund skills, enable exchanges and let communities lead. The rest will follow.

“We thought we needed the internet. What we really needed was confidence, tools and time.”

— Athi Community Network Team

Rebecca Ryakitimbo is a feminist technologist and researcher working at the intersection of AI, gender justice and digital equity. She supports feminist tech spaces such as the African Women School of AI and curates the Gendering AI conference. As part of LocNet, she supports community-centred connectivity initiatives by facilitating communities of practice and researching community-centred connectivity and local services for equitable, locally led digital ecosystems.

The experience shared in this blog was supported by the Local Networks (LocNet) initiative through a cycle of microgrants made available via a closed call to the initiative's partners and community networks in Brazil, Indonesia, Kenya and South Africa. Learn more about the call here.