Women human rights defenders (WHRDs) have long been at the centre of struggles for justice, democracy, and freedom – from resisting authoritarianism and defending land to advancing gender rights and digital freedoms, benefiting entire communities. Yet these very defenders are systematically targeted and under-resourced in the current realities of the world as repression fuelled by authoritarianism and the surge in anti-rights narratives are steadily rising.

This contradiction of WHRDs being essential yet systematically undermined was at the centre of APC’s Safety for Voices webinar, Digital repression, WHRDs' safety and movements' sustainability, held on 24 September 2025. The discussion brought together WHRDs, feminist organisers, researchers and digital rights advocates from Asia, Latin America and the SWANA (Southwest Asia and North Africa) to reflect on the rising threats of digital repression, the political weaponisation of safety, and the urgent need for sustainable resourcing of movements.

Repression by design

Speakers at the webinar highlighted that repression is not incidental but systemic. States are deliberately weaponising laws, technologies and platforms to dismantle movements and silence dissent.

Shmyla Khan, a researcher on human rights and gender, said, “The states have accumulated so many tools to entrap people, with no guardrails stopping this repression both offline and in digital spaces. A lot of this is happening in the shadows where we don’t know the true extent of how this repression and narratives around it are being built.” She added that anti-gender forces are actively working to undermine sustainability.

“They are going after the sustainability of movements. Not only to dismantle movements, but also systemically strengthen the dominant opposing narratives.”

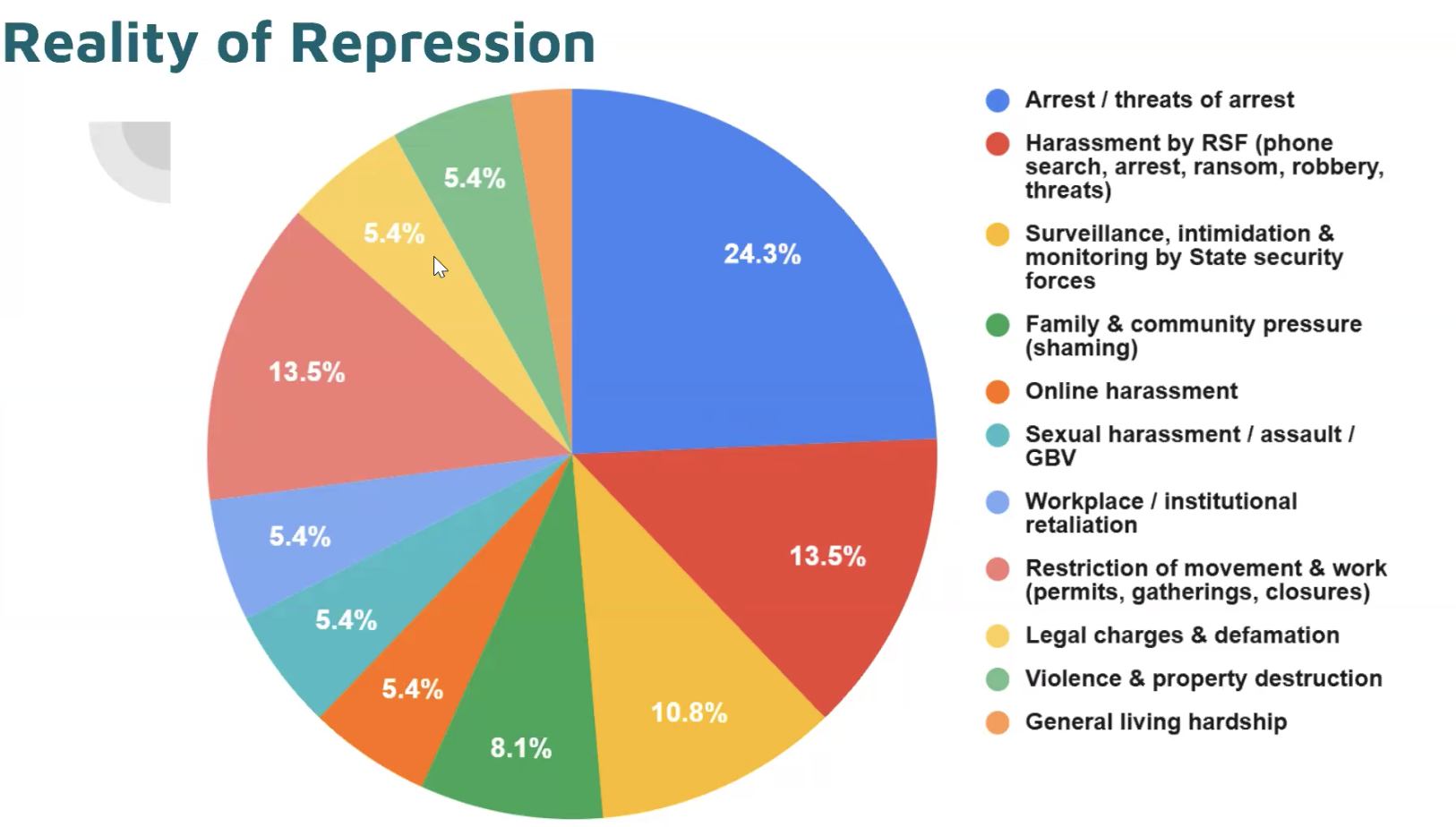

For WHRDs, this repression is deeply personal, and impacts their lives and of the people around them. Tesneem Elhassan, a Sudanese feminist researcher, explained, “Digital aggression can be seen clearly in Sudan. Lots of doxxing, tracing people online. If you say anything criticising [the] Sudanese armed forces, you can be charged with treason.” Most respondents to a survey Tesneem conducted said they have either been arrested or threatened with arrest for their activism in Sudan.

The consequences of these arrests extend beyond their activism, and into their personal interactions with their communities. “As a WHRD, if you’re arrested, it leads to social isolation. Your own community treats you as if you’re a shameful person.” This social isolation is then further felt by the families and friends of WHRDs who are also harassed.

Graph from Tesneem Elhassan’s survey "Between Erasure and Resistance: Women’s Bodies, Memories, and Narratives under Sudan’s Fascist Islamist Regime", presented during the webinar.

As a result, Tesneem said, many WHRDs choose to either work in the shadows or completely stop their activism out of fear of this violence.

Weam Shawgi, a Sudanese feminist activist, said, “There’s a systemic attempt to disconnect us from each other.”

Survival is not sustainability

A recurring theme during the webinar was the distinction between resilience and sustainability. WHRDs may continue to resist, but survival under constant attacks cannot be conflated with building sustainable movements.

As Shmyla questioned, “Are we meaning to sustain what we have right now?” She added, “We have a very unsustainable model. Overworked people under repression will eventually give up given the pressure through legislation and suppression. This is by design.”

Tesneem said in agreement, “What is going on in Sudan is not sustainable, we’re in survival mode. Resilience is not equal to sustainability. WHRDs can’t organise without safety, which is inseparable from collective political action.” She emphasised the need for long-term solutions, and to start with, said “recognition of activists’ labour as political and not charity or voluntary work” is essential.

Weam painted a stark picture of life under siege in Sudan, and raised questions about the conditions they expect sustainability in.

“We don’t have a voice now because we are afraid for our lives. We’re banned from going to our own countries. Many can’t have access to a passport. We can’t meet each other. We don’t have an economic system; no internet for the past two years. People can’t organise in these conditions.”

Despite these realities, she pointed to the courage of Sudanese activists who continue to explore new strategies, even if that means retreating from digital spaces. “Revolution has been giving us new ideas for survival – let’s stop using social media, let’s stop putting our photos online.”

The discussion reaffirmed that digital repression is not just a technical issue but also a political weapon. Safety cannot be seen as an apolitical service but must be recognised as a political condition for movement-building.

As Ashi, a digital security coordinator at Front Line Defenders working in Latin America, shared during the discussion, “It’s important that we don’t see digital and holistic security as separate from political action.” She added, “Digital security looks very individual, but it's a collective holistic protection.”

Giving an example of various vulnerabilities that WHRDs in particular, and women in general, live with, Ashi said, “Women are often expected to share their devices with family members, which means that they are now vulnerable because they have to lower their digital security measures [to accommodate their family usage].” She reflects that the same expectation is not placed on men in the house. “There is an intentional gender gap in tech, which puts them in vulnerable positions.”

Funding models as part of the problem

The event created space for discussion of funding models and the power structures they project. Feminist organising faces growing threats amid major shifts in global funding. As a result, grassroots WHRD-led groups are struggling to survive, trapped in cycles of emergency response without long-term, flexible support.

In a constrained environment, the conversation turned to the failures of current donor and funding models, which often reproduce the very hierarchies that movements seek to dismantle. In the current climate of funding cuts, short-term projectisation, and donors’ shifting priorities and complete retreat from gender justice movements, these limitations are amplified.

“We need to question the hierarchy in the funding spaces. A lot of who gets access to donor spaces, and who gets to decide how to use the funding, is dependent on class structure. These are difficult questions, but important,” Shmyla reflected.

She challenged the obsession with outputs over systemic change in these structures.“Funding is often skewed, dependent on capitalist structures focused on productivity. ‘What do you have to show for it?’ When you talk about social change, it’s a ridiculous exercise to ask someone to report on it with annual reports. Fundamentally, it doesn’t lead to movement-making. It’s all very power-centric.”

Weam highlighted the limitations of bureaucratic funding and called for grassroots-led alternatives. “We don’t need bureaucratic funding that is not sensitive to the needs of the communities. We should be able to fund our movements from our grassroots organising. We don’t need to have a meeting in another country; we can have it online, and put that money in organising and in movements.”

For Tesneem, sustainability requires donors to rethink impact itself. “Funding has to be about the context. It’s not about how much you give, but about the impact. We know grassroots people who are actually doing the work on the ground, but don’t have access to the resources.” She emphasised various other ways that movements can be sustained beyond just financial resources that come with a lot of expectations of capitalist models of reporting. She said, “Funding doesn’t always have to be money – it can also be a series of training and educating people, equipping them with the skills to navigate their realities.”

For Ashi, sustainability in funding is especially urgent in the tech space.

“We need more sustainable funding, especially in digital security spaces. Tech is evolving, but our needs are the same ones – fighting the same fights. We need to find funding that links different impacts, like digital security and environmental impacts.”

Towards collective safety and solidarity

The panellists in this conversation made it clear that solidarity must go beyond rhetoric. WHRDs are demanding not survival but sustainability based on long-term, flexible and care-centred resourcing that recognises their labour as political and essential. As states entrench authoritarian practices and donors redirect resources elsewhere, movements are forced to ask the hard questions. Who is being left behind in donor agendas? What does sustainability look like in the current political landscape? What kind of sustainability is worth pursuing? How can feminist solidarities across regions push back against both authoritarian repression and a funding model that rewards short-term productivity and sidelines feminist organising?

APC’s Safety for Voices initiative will continue to create spaces where WHRDs lead these analyses, and where donors are invited to listen, reflect and transform how solidarity is practised. Because, as this discussion reminded us, resourcing feminist movements is not just a funding “theme”.